During the celebration of its 75th Anniversary, the national headquarters of the National Junior College Athletic Association (NJCAA) released nine insightful articles during the 2012-13 academic year that comprised the NJCAA 75th Anniversary Feature Series. Below is the fourth nstallment of the series, which was also published in the NJCAA Review.

by Michael Teague, NJCAA Media Relations

Entering the 1970s, the NJCAA personified the environment of the United States as a whole. Decades of struggles, followed by decades of renovation brought the organization and the country to a critical point in history. Vast success and flourishing revenues were being felt across the landscape, except in the case of women.

According to the Census Bureau, women on average earned 57.9 percent of what their male counterparts earned in 1972. A study by the National Coalition for Women & Girls in Education showed that during the 1971-72 academic year, only nine percent of medical school graduates and only seven percent of law school graduates were women. In that same year, only 29,972 women in the entire nation participated in varsity college sports.

“At almost all universities in the United States of America, the men had wonderful opportunities to compete at both the high school level and collegiate level,” said former University of Iowa athletic director Dr. Christine Grant. “Women were being discriminated against on two fronts. They were denied access to real varsity competition – which in itself was truly unfair – but in addition to that, all students at the university level helped subsidize the participation opportunities for the men. The women were subsidizing the same opportunities for the men that they were denied.”

Despite the male-dominated stratification of the early 70s, most of the inequality in collegiate athletics during the era was created by the predetermined gender roles of American culture. As a Scotland-native, Grant was taken aback by the lack of opportunities for women when she moved to the United States.

“The opportunities for young men were absolutely fantastic and there was nothing comparable for young women,” Dr. Grant said. “When I asked why this was happening, their response was, ‘Young women aren’t interested in sports.’ I had been playing sports since I was 11 and had participated in international sports so I knew that was a load of hogwash, but they truly believed that women weren’t interested.”

For the few women who did participate in collegiate athletics at the time, it was a far cry from the sports environment that male student-athletes enjoyed.

“The girls in high school had almost nothing and the young women at the university level only had club sports for which they had to pay,” Dr. Grant said.

Everything changed on June 23, 1972, when President Richard Nixon signed into law the single most important piece of legislation for collegiate athletics in America: Title IX. The 37 words contained in the portion of the Education Amendments of 1972 completely changed the face of sports in this country.

Everything changed on June 23, 1972, when President Richard Nixon signed into law the single most important piece of legislation for collegiate athletics in America: Title IX. The 37 words contained in the portion of the Education Amendments of 1972 completely changed the face of sports in this country.

For many male athletic administers across the nation, the passage of Title IX meant an end to the sports world as they knew it. Several distinguished icons of collegiate athletics fought tooth and nail against the implementation of the law, including legendary Texas football coach Darrell K. Royal who drafted an amendment to exempt revenue generating sports from complying with the statute.

“The men were very fearful of women entering their domain,” said former Southern Illinois University athletic director Dr. Charlotte West. “They were not very receptive and they fought Title IX and they fought us.”

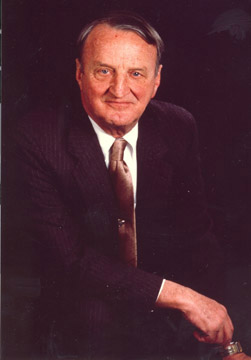

While numerous men stood in defiant opposition to Title IX, NJCAA executive director George Killian perceived things in a different light. Killian saw an opportunity. An opportunity that he would have to substantiate with his colleagues in the NJCAA.

“In the beginning, people thought I was nuts,” Killian said. “Budgets were small and the men had a certain amount of dollars that they didn’t want to share with somebody else. They saw this as taking over a segment of collegiate sports that would take money away from the men. Our guys didn’t want anything to do with it. These were not stupid guys. They were my friends. It was just the culture of the time. So I kept sitting there every day, thinking about how I would convince these guys.”

Killian realized that if he was going to garner the support to bring women’s athletics into the NJCAA, it was the school presidents that he would need the backing of. In 1972, Killian formed the Presidents’ Special Study Committee to analyze the prospect of adding a separate division for women within in the NJCAA.

“I knew that if we got the presidents to say it was a good move, then we could get this done,” Killian said. “We brought them to Hutchinson and explained to them everything in detail. They thought it was a great idea and that’s all we needed, the support of the presidents.”

The committee followed their study by sending out a questionnaire to the membership to measure the level of interest in creating a women’s division. Clear support for the move was echoed in the membership’s response.

With the endorsement of the presidential committee and the general support of the membership, Killian moved on to his next challenge: convincing the women to join. At the time, most of women’s collegiate athletics was overseen by the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW).

With the endorsement of the presidential committee and the general support of the membership, Killian moved on to his next challenge: convincing the women to join. At the time, most of women’s collegiate athletics was overseen by the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW).

“One of the biggest challenges we faced was getting the women to come with us,” Killian said. “It wasn’t easy because the AIAW had a group of strong women from community colleges. Everyone was extremely nervous about the AIAW. The biggest threat was them taking complete command of women’s athletics. If the men and women at a college were in separate organizations, they could fight over dollars.”

Trying to convince the women to leave an association that specialized in women’s athletics was no easy task. Killian decided that there was only one way to combine men’s and women’s athletics under one organization. They had to be equal.

“I thought the only way we could do that was to present a plan that was equal to what the men did,” Killian said. “If we were going to take the women in, we had to make sure the men didn’t lose any money. That’s why it was equal and the money was split in half. The word equal was very important. Everything had to be equal, so if you paid $250 for the men then you paid $250 for the women. If the women spent $1,000, it came out of their half. If the men spent $1,000, it came out of their half.”

Equality in finances also meant equality in voting. With 16 male region directors each having a vote in organizational legislation, there needed to be 16 female region directors with the same voting power.

“Equality in voting was the only acceptable avenue for women to be empowered to direct their own destiny for women’s sports,” said former St. Louis Community College-Florissant Valley athletic director Lea Plarski. “As members of a parent organization without voting rights, we would have had minimal influence on the direction of women’s programming. The men’s division would have held the decision-making power and nothing would have been gained through realignment with the NJCAA.”

With the assurance of across-the-board equality, the female administrators recognized the advantages of joining an organization that had established itself as the nation’s leader in two-year collegiate athletics. Despite the AIAW’s niche for women’s athletics, the association was lacking when it came to finances, support for competitions, travel, facilities, visibility and promotion.

“They saw that we had a strong organization that was in business since 1938,” Killian said. “We had a program that everybody could see and we had the support of college presidents. The women understood that we had more expertise in how to run championships and departments.”

“They saw that we had a strong organization that was in business since 1938,” Killian said. “We had a program that everybody could see and we had the support of college presidents. The women understood that we had more expertise in how to run championships and departments.”

“The AIAW provided a starting place for organized women’s collegiate athletics,” Plarski said. “The NJCAA welcomed the women’s division, gave it a home, elected and appointed women to positions of leadership, provided programming on equal footing with the men’s division, promoted visibility for female student-athletes and coaches, leveled the playing field in regards to rules and regulations and generated respect for competition for women in two-year schools that otherwise had been overlooked or minimized in importance.”

The deciding factor for the women to come on board hinged on the all too familiar dilemma of the needs of two-year colleges being ignored for the desires of four-year schools. Although women enjoyed being a part of an organization dedicated to women’s athletics, the unique challenges facing two-year programs were not being addressed by the AIAW.

“The women that wanted to join spoke up for us,” Killian said. “They didn’t criticize. Their biggest argument against the AIAW was that they were primarily a four-year institution. Coming from two-year schools, they realized they had to watch out for themselves.”

“A perception that the two-year school had a limited voice in the AIAW was prevalent among NJCAA representatives,” Plarski said. “Within the AIAW, two-year schools seemed to be at the bottom of the pecking order without opportunities for key leadership roles within the overall membership.”

After Killian addressed the concerns of the women, all that was left to do was put pen to paper. At the 1974 annual meeting, the NJCAA decided to invite a female representative from each region to the 1975 meeting to organize the nation’s first women’s division within a coed collegiate athletics organization. In the meantime, national invitational tournaments for women’s volleyball, basketball and tennis were created for the 1974-75 academic year.

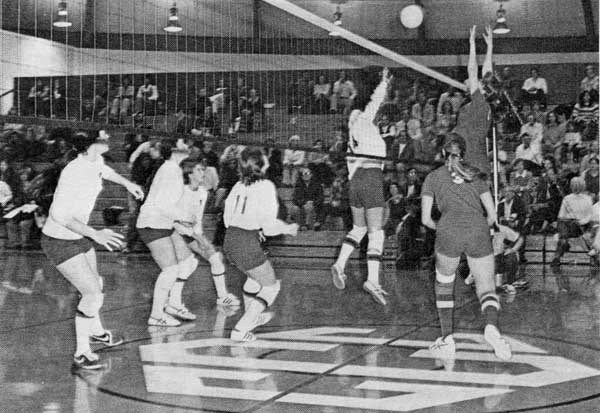

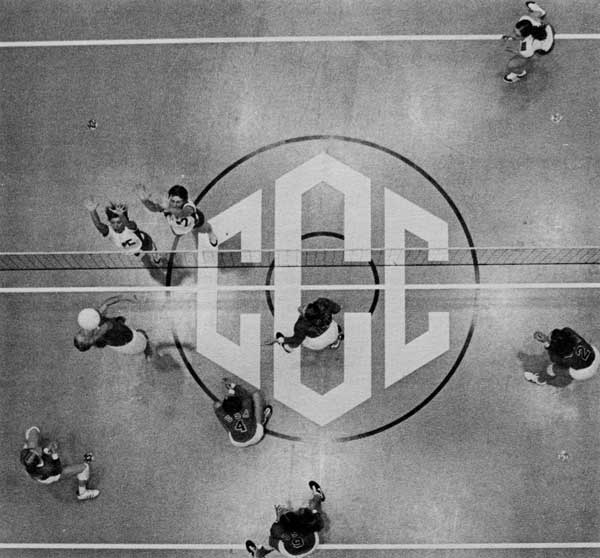

Following successful management of the three invitational tournaments and formation of the women’s division, the NJCAA reclassified all three events as national championships. In November of 1975, the NJCAA Women’s Volleyball Championship became the first championship held for women by a national coed collegiate organization. The National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) wouldn’t have their first women’s championship until 1980, followed by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) who had their first in 1981.

Following successful management of the three invitational tournaments and formation of the women’s division, the NJCAA reclassified all three events as national championships. In November of 1975, the NJCAA Women’s Volleyball Championship became the first championship held for women by a national coed collegiate organization. The National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) wouldn’t have their first women’s championship until 1980, followed by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) who had their first in 1981.

The precedent set by the NJCAA completely changed the picture for both the NAIA and NCAA. The NAIA quickly worked to establish their women’s division but the conservative administrators of the NCAA would take some persuasion. NCAA executive director Walter Byers had a strong relationship with Killian and once he saw that the AIAW was a serious threat to the NCAA, he turned to him for help with this issue.

“Walter would call me asking what I thought,” Killian said. “I told him he had to make sure he had a couple of strong presidents in his corner. That’s what he did. He needed people like the athletic director at Michigan, Don Canham. Don Canham was an icon so when he spoke, everybody listened. He got those kind of people to push the program and he did it.”

By 1979, the NJCAA had added women’s national championships for cross country, swimming & diving, gymnastics, indoor track & field, outdoor track & field and softball and invitational tournaments for field hockey, bowling, skiing and golf. The NJCAA quickly became Byers’ most convincing argument for a women’s division to his NCAA peers.

“The one thing that helped the NCAA move forward is that we were still in business,” Killian said. “We were actually having a women’s division and were still in business.”

Having already blazed the trail for women’s collegiate athletics, the NJCAA continued to be at the forefront of increasing the opportunities available to women. After serving as the NJCAA Vice President for Women for 15 years, Plarski was elected as the organization’s first female president in 1990.

“It was an honor to be elected,” Plarski said. “From the very beginning, I felt trust, respect and support. I never had the feeling that lines had been drawn, even though a small pocket of regional directors still resisted the women’s division. When it came to resolving difficult issues, we were a united house making decisions for the good of the organization.”

In July 2009, the NJCAA set another milestone for women in sports when Mary Ellen Leicht was named the association’s executive director. Leicht is the first and only female chief executive of any national collegiate athletics organization in the United States.

In July 2009, the NJCAA set another milestone for women in sports when Mary Ellen Leicht was named the association’s executive director. Leicht is the first and only female chief executive of any national collegiate athletics organization in the United States.

“I’m honored to have my current position with the NJCAA and know that it would not have been possible without some tremendous role models in my life,” Leicht said. “Becoming the first female executive director of a collegiate athletics organization has been quite challenging – not because of my gender but because of the demands of the position itself. It’s not about being a female executive director. It’s about those that created the path which has allowed me as a female to retain the position of executive director.”

The number of women playing varsity sports in college increased 622 percent between 1971-72 – the year before Title IX was instituted – and 2009-10. The NJCAA alone had 21,862 female student-athletes competing on 1,821 teams in 2011-12. Despite the tireless efforts of the NJCAA’s key leaders in this movement, Title IX was the lynchpin that held it all together.

“Somewhere along the line it would have come about but it wouldn’t have come as quickly,” Killian said. “Title IX shoved it out there, but if we waited for everyone to get together it would have been 20 years before something happened.”

“Title IX provided the legal thrust for the establishment of athletics programs for girls and women at all levels,” Plarski said. “Significant credit must be given to Title IX and the pressure it generated to equalize athletic opportunities for student-athletes enrolled in the same institution.”

“Title IX provided the legal thrust for the establishment of athletics programs for girls and women at all levels,” Plarski said. “Significant credit must be given to Title IX and the pressure it generated to equalize athletic opportunities for student-athletes enrolled in the same institution.”

Although Title IX helped to level the playing field at public institutions of higher learning, there is still a large gap in opportunities provided to women. According to a 2012 study by Brooklyn College, women only make up 20.3 percent of athletic directors and 9.8 percent of sports information directors, while 9.2 percent of athletic departments in America had no females in administrative positions. The report also showed that only 42.9 percent of women’s college teams are actually led by a female head coach and 68.8 percent of women’s head coaching jobs have gone to men since 2000.

“We’ve seen all this wonderful growth for female athletes with a concurring downward trend on the number of women coaching women’s teams,” West said. “I think the way to improve that is to educate people about this downward trend and follow the lead of organizations like the Alliance of Women Coaches. They talk to the women coaches about getting more people involved and reaching out to encourage young women interested in sports to be coaches.”

There is still a lot of work to be done but the NJCAA continues to follow the proactive philosophy it’s utilized for 75 years.

“The NJCAA is a special group of people that have endured a lot of adversity,” Plarski said. “We’ve always worked together. The tug-of-war is always in the direction of how the organization can be improved.”

When push comes to shove, it all comes down to the NJCAA’s dedicated leaders and members. It was the forward-thinking individuals at all levels of the NJCAA that brought women’s collegiate athletics into the mainstream. The individuals that stood in the face of adamant opposition and fought for gender equity in collegiate athletics.

“It’s taken a hell of a lot of people, men and women, to get the women’s division to where it is today,” Killian said. “If you don’t have strong support across the country, it’s not going to work. You need men and women working together.”