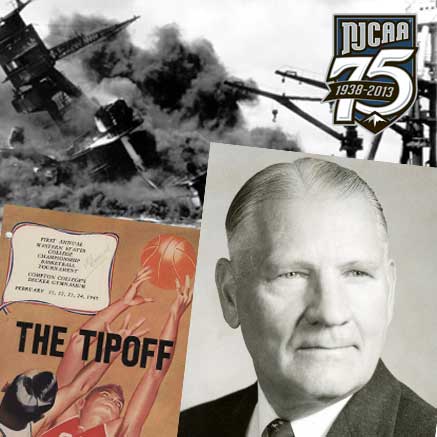

During the celebration of its 75th Anniversary, the national headquarters of the National Junior College Athletic Association (NJCAA) released nine insightful articles during the 2012-13 academic year that comprised the NJCAA 75th Anniversary Feature Series. Below is the second installment of the series, which was also published in the NJCAA Review.

By Michael Teague, NJCAA Media Relations

Today’s NJCAA is a steadfast pillar of two-year collegiate athletics that provides opportunities for over 58,000 student-athletes at over 520 member institutions. However, no organization that has endured 75 years of existence has done so without overcoming seemingly insurmountable odds.

From 1941 to 1959, the NJCAA faced several daunting challenges that threatened the very existence of the association. Standing on a foundation of strong leadership, and support from its membership, the NJCAA stared down adversity and came out the other side as the leader in junior college athletics.

Following its inception in 1938, the NJCAA membership quickly expanded across the California landscape. In response to this rapid growth, the organization divided its members into four geographic regions within the state.

Two more regions would be added in 1940 and another in 1941 to account for the growing number of members located outside the Golden State. In May of 1940, the second annual NJCAA Track & Field Championships welcomed in the first competitors from outside the state of California. The NJCAA continued to extend its reach by relocating the 1941 championships to Denver, Colo., where schools from nine different states participated.

Everything looked to be headed in the right direction for the NJCAA going into the fall of 1941. Four years of continued growth, organization and success, however, was abruptly brought to a halt by an event in American history that will live in infamy.

On December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy bombed the United States naval base located in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Throwing the nation into World War II, the catastrophic event led to 10 million American men being drafted into the United States military and delivered a crippling blow to the junior college community.

Limitations on resources, travel and personnel led to the NJCAA terminating operations following the 1942 Track & Field Championships.

Despite the devastating affect that entering World War II had on two-year colleges in America, the subsequent response by the U.S. Government would start a community college movement that continues to this day. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 – informally known as the “G.I. Bill” and signed into law by President Roosevelt in 1944 – led to a spike in college attendance. By the fall of 1946, more than one million American veterans from the Second World War enrolled in college. The number of junior colleges in the nation jumped to 663, facilitating 455,048 students.

As life in America began to return to normal, talk of reviving the NJCAA began at the 1945 Western States College Championship Basketball Tournament. Since all nine participating schools had been NJCAA members, discussions led to the scheduling of the fifth NJCAA annual meeting in May 1946.

As life in America began to return to normal, talk of reviving the NJCAA began at the 1945 Western States College Championship Basketball Tournament. Since all nine participating schools had been NJCAA members, discussions led to the scheduling of the fifth NJCAA annual meeting in May 1946.

Over the next two years, interest in the NJCAA skyrocketed as the organization added championships for swimming, tennis, golf and basketball. In March 1948, the NJCAA hosted their first ever National Basketball Championship Tournament featuring sixteen schools from the newly formed eight regions across the country. Held in conjunction with the tournament at Southwest Missouri State Teachers College, the NJCAA’s seventh annual meeting drew representatives from 23 schools in 14 states. The increasing popularity and notoriety of the organization necessitated the NJCAA’s expansion to 16 regions for the 1948-49 academic year. By March 1949, NJCAA membership had grown to 207 schools in 38 states.

The incredible influx of members in such a short time span started to shed light on the NJCAA’s lack of leadership, communication and resources. What was once a small, loosely-governed affiliation of schools in the West was now a nation-wide hodgepodge of institutions with no central authority. Recognizing the need for a strong governing body, the NJCAA formed the Committee on Reorganization at the 1949 annual meeting.

Part of the restructuring process that took place at the 1949 meeting was the election of a new president. The NJCAA turned to Weber College (Utah) athletic director and head basketball coach Reed K. Swenson. Having served at those positions since 1933, Swenson had developed a reputation within the NJCAA leadership as a capable man for the position. However, even Swenson himself was surprised by the level of disarray the organization was in.

“Had I known the mess that the NJCAA was in, I might not have accepted the position,” Swenson later said jokingly.

One of the greatest obstacles that Swenson and the NJCAA faced was the growing discontent of the California colleges that had been the association’s foundation since its creation in 1938. The organization’s push for expansion across the map frustrated Californian administrators who felt that travel costs to national tournaments outside the state would be too high. Following the assumption that the national competitions often pitted California schools against each other anyways, the California State Athletic Committee took action with a recommendation for withdrawal.

One of the greatest obstacles that Swenson and the NJCAA faced was the growing discontent of the California colleges that had been the association’s foundation since its creation in 1938. The organization’s push for expansion across the map frustrated Californian administrators who felt that travel costs to national tournaments outside the state would be too high. Following the assumption that the national competitions often pitted California schools against each other anyways, the California State Athletic Committee took action with a recommendation for withdrawal.

In November 1950, the California Junior College Association approved a measure banning state colleges from participating in NJCAA sponsored contests beginning Sept. 1, 1951. Having 43 members in the Golden State, the NJCAA saw its membership plummet from 185 in 1950-51 to 137 in 1951-52. Despite the strong support that the resolution gained, not everyone in California believed it was the right course of action.

“As I see it, it will only be the Golden State colleges that are hurt by this action,” said Compton College athletic director Earle J. Holmes. “It will really strengthen the National Association as it will give other regions, where the junior college athletic program is just getting started, a better opportunity to place in championship activities.”

Holmes was right. Despite the momentary loss of programs following the California departure, the NJCAA quickly rebuilt its membership to 187 schools in 1955-56. By 1959-60, the NJCAA’s reach extended to 246 colleges in 37 states.

While dealing with the California issue in the early 1950s, the NJCAA was also defending an attack from another front. The American Association of Junior Colleges (AAJC) had growing concerns regarding the state of junior college athletics and in 1950 strongly discouraged participation in intersectional playoffs and national competitions.

However, the AAJC soon realized the need for national governance of two-year collegiate athletics due to increasing athletic costs, subsidation of student-athletes, travel distances and corruption. In response, the NJCAA completely reorganized its structure and significantly strengthened its eligibility rules in 1950.

Another major step the NJCAA took to create a more efficient governing body was the creation of “A Statement of Guiding Principles for Conducting Junior College Athletics”, also known as the Dallas Code. This statement – jointly accepted by the AAJC and NJCAA in 1953 – set forth several objectives that established the NJCAA’s authority over the increasingly large association. For the first time in its existence, the NJCAA finally had a common and clear set of goals that its members could follow.

As the 1950s drew to a close, the NJCAA had reestablished itself as one of the premier intercollegiate organizations in the nation. As the membership and number of sponsored sports continued to grow, the NJCAA’s success was clearly noticed by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA).

“This association’s executive committee has discussed the growth of junior college athletic programs in this country and the increasing contacts and liaison between the athletic officials of four-year and two-year institutions,” said NCAA Executive Director Walter Byers in a letter to NJCAA Secretary Hobart Bolerjack. “It was our executive committee’s conclusion that it would be advantageous to both organizations if the officers of the NJCAA and NCAA were to get together for informal discussions at some mutually convenient time and place.”

“This association’s executive committee has discussed the growth of junior college athletic programs in this country and the increasing contacts and liaison between the athletic officials of four-year and two-year institutions,” said NCAA Executive Director Walter Byers in a letter to NJCAA Secretary Hobart Bolerjack. “It was our executive committee’s conclusion that it would be advantageous to both organizations if the officers of the NJCAA and NCAA were to get together for informal discussions at some mutually convenient time and place.”

Recognizing the advancing opportunities that surrounded two-year collegiate athletics, the NCAA began assessing the possibility of creating a junior college division. In March 1959, the NCAA sent out a questionnaire to 273 junior colleges to discover the membership’s interest in joining the larger association. In response, the NJCAA – now a diligent, organized association – actively engaged their members in the conversation.

“We believe that any junior college program, athletic or otherwise, should be administered by junior college people,” Swenson said in April 1959. “We believe that junior college presidents and athletic directors can more capably administer intersectional and national athletic competition for the junior colleges than the NCAA, which is primarily designed to serve the needs of the large four-year colleges and universities.”

Receiving the message wholeheartedly, NJCAA member schools sent the NCAA a resounding message that they wanted to be governed by an organization specializing in two-year collegiate athletics. The membership’s message was summed up by more of Swenson’s statements in April 1959.

“We are willing and anxious to work with the NCAA or any other athletic organization to further common ideals and purposes,” Reed said, “but strongly resent intrusion by unilateral action.”

The strong response sent by the NJCAA membership rang loud and clear with the NCAA who decided to no longer pursue a junior college division. This event solidified the NJCAA’s position as the sole leader in junior college athletics.

As Weber College became Weber State – a four-year institution – it became time for Swenson to relinquish his office with the NJCAA. Despite his tireless efforts, Swenson refused to take credit and attributed the organization’s success to the people who supported it in a farewell letter to the membership in the spring of 1962.

“As I survey the significant features of the past few years,” Sweson said, “I would first list the unselfish and dedicated efforts that hundreds of men have contributed to the growth of junior college athletics.”

After nearly two decades of struggles and turmoil, the NJCAA entered the 1960s with an impenetrable foundation built by both its membership and leadership. By the time Swenson stepped down from his post in 1962, he had cleared every hurdle in the way and had paved a pathway to success for the NJCAA in the years to come. Perhaps the strongest indictment of Swenson’s leadership was summed up by his successor, Gerald D. Allard.

“When Reed took over as president, dissension was a serious problem.” Allard said in the September 1962 issue of JUCO Review, “Personality clashes and sectional jealousy prevented real progress at annual meetings. In his quiet and persuasive manner, Reed molded the group into a team which worked for the welfare of the whole Junior College Athletic Program. If he had made no other contributions this would have warranted his being called an outstanding president.”

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the NJCAA proved that it could overcome any level of adversity with devoted governance and sound support from its member institutions. That formula for success continues to this day as the NJCAA faces every challenge with a united coalition of dedicated individuals working towards a common goal.